The prognosis (chance of survival) for small cell lung cancer depends on the stage at diagnosis. Healthcare providers have more success treating cancer that has not spread far when it is diagnosed at an early stage.

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of small cell lung cancer. It is produced by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI.

Stage of Lung Cancer

If you have been diagnosed with lung cancer, your doctor will want to know the stage of the tumor in order to plan the best treatment for you. The stage of a cancer tells doctors how much the cancer has grown into your body and whether it has spread to other parts of the chest or elsewhere in the body.

The stage of your cancer is based on the results of tests done before you begin treatment, called pretreatment staging. Your doctor will assign a number to your stage based on the information from those tests, as well as from the results of lung biopsies and other clinical examinations. Your doctor may also give you the stage of your cancer in words, such as local, regional or distant.

Stage 1 is the earliest stage of small cell lung cancer, when abnormal cells only affect the lining of the air passages in your lungs. Your doctor may also call this stage squamous cell carcinoma in situ, or SCCIS. In stage 1, the tumor is 3 centimeters (cm) or smaller and has not spread to lymph nodes inside or outside of your lungs.

In stage 2 of lung cancer, the tumor has gotten larger but it hasn’t spread far from where it started in your lungs or to nearby lymph nodes. The stage of your lung cancer can be further divided into substages, depending on the size of your tumor and how far it has spread.

A cancer that has spread from the area in your lungs to other areas of the chest, such as the lymph nodes on the same side as the tumor, is called stage 3 of lung cancer. Your doctor might also describe the stage of your cancer as limited or extensive.

When your cancer has spread beyond the area in your chest to other parts of your body, it is said to be in stage 4. This is called metastatic or advanced cancer. Those areas might include the liver, adrenal gland or bone. Your doctor might be able to treat your cancer with chemotherapy or other therapies, depending on where the cancer has spread.

Lung Biopsies

During lung biopsy, your doctor takes out a small sample of tissue that contains cancer cells and sends it to a lab for testing. Your doctor may recommend this test to decide the best treatment for your case. The results are usually ready within a week. Before the procedure, your doctor may give you blood tests and ask if you are pregnant or have any allergies. You will also need to sign consent papers.

You might need to remove your clothes and put on a hospital gown. Then, you lie down on the test table. An IV (intravenous) line will be put into a vein in your arm or hand and an X-ray or other imaging test will be done to find the exact biopsy site. Then the area will be cleaned and marked.

This is the most common type of lung biopsy. It is used to find out whether a lump or nodule is cancer and what kind of cancer it is. Your doctor will use a special needle that goes into your chest between two ribs to take a sample of the lung tissue. You may feel some pain or pressure, but this shouldn’t be severe. You will get medicine to help you relax during the biopsy. The doctor will watch your heart rate, blood pressure and breathing during the test. You will be on oxygen through a mask or tube during the biopsy and for some time afterwards.

Sometimes a needle biopsy can move cancer cells to another part of your body, which is called seeding. This rarely happens, but if it does, you should call your doctor right away.

Sometimes your doctor will treat the area where the biopsy was with radiation or chemotherapy. This can reduce the chance of the cancer coming back or spreading to other parts of your body. The radiation or chemotherapy can be given after surgery or as an alternative to surgery. Your doctor can give you chemotherapy by mouth or into a vein (intravenously). It works by killing or stopping the growth of cancer cells. It might also kill cancer cells that can’t be seen in an X-ray or other test.

Lung Imaging

Lung imaging (CT, MRI, and X-rays) helps doctors find out the stage of SCLC. They also help them plan treatment. The tumors in the lungs are viewed by CT and MRI to check for the size of the cancer, whether it has spread to other parts of the lung or body, and to identify if there is fluid (pleural effusion) around the cancer.

In general, the prognosis for people with small cell lung cancer is poorer than for those with non-small cell lung cancer. However, everyone is different and survival depends on several factors. Some of the important factors are the person’s performance status, smoking history, and the extent to which the cancer has spread at diagnosis.

The doctor may order other tests to see how well the treatment is working or to find out if cancer has come back (recurs). If it does, the treatment plan will change. For example, the doctor might prescribe medicine to reduce the chance that the cancer will return or another type of surgery.

If a person is very sick, the doctor may use point of care ultrasound (LUS) to find out if the cancer has spread within the lungs or to other organs in the body. LUS is easy to use, provides a quick and accurate result, and does not involve any ionizing radiation.

Some studies are looking at using LUS to predict how a patient will do after treatment. This is called radiogenomics, which tries to match the molecular makeup of the tumor with what is known about how it will respond to certain types of treatment.

In some cases, small cell lung cancer will recur (come back) after it is treated. If the cancer returns, the doctor will treat it differently depending on where it comes back and how far it has spread. For more information, see the booklet Recurrent Cancer: When It Comes Back.

Laboratory Tests

The results of laboratory tests can help doctors confirm a diagnosis of small cell lung cancer and determine how far the disease has spread. The information gathered from these tests is also used to stage the cancer, which helps doctors plan treatment.

Several blood tests may be done to check your general health and to find out how well your treatment is working. These include a complete blood count, a chemistry panel that includes liver function tests (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine) and a kidney function test (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine). In addition, the doctor will ask about your family history of lung cancer. This can help them look for genetic mutations that might be a cause of the disease.

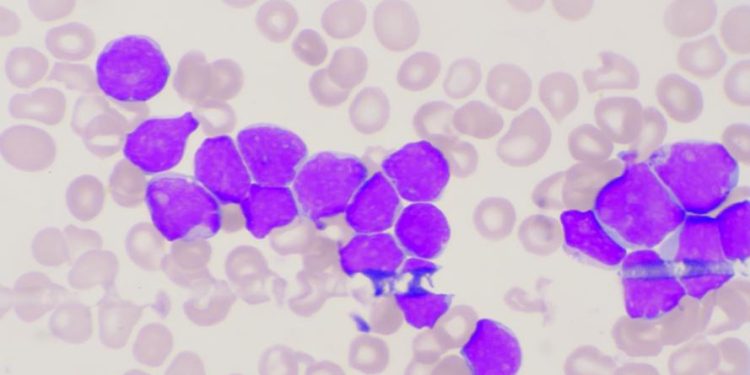

A tissue sample obtained during a biopsy of a lung, lymph node or metastasis is examined under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis of small cell lung cancer. A pathologist – a doctor who studies diseases in the laboratory – will use techniques such as immunohistochemistry to examine a tumor sample for special markers on cancer cells that can be detected with a special dye or radioactive material.

Depending on your symptoms, your doctor may recommend a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This is a non-invasive procedure that uses magnetism and radio waves to create detailed pictures of body tissues, including soft ones such as the brain. MRI scans show more detailed images than CT scans do, and they can detect some types of tumors that aren’t visible with other tests.

In some cases, your doctor may want to do a computed tomography angiogram (CT angio) to get more detailed information about the location and size of a tumor in your lungs or in other parts of your chest. These procedures involve X-rays of the arteries in your chest. They can help your doctor decide what type of surgery might be best for you.

During a minimally invasive surgical procedure called video-assisted thoracic surgery, or VATS, your doctor can remove a small part of the lung affected by small cell lung cancer using a thin tube with a camera and a tool at the end of it. The doctor can also place tiny “fiducial markers,” which are visible with imaging scans, on the tumor to guide future treatments such as stereotactic body radiation therapy, in which energy beams are directed at the tumor to destroy it.